An Innovation Study: The Economist

What big media brands, or other business moguls in a declining market, can learn from the strategy and tactics that ensured that this English print giant became a user-first digital-oriented company.

The Meltdown

Many traditional markets have been disrupted over the last decades of digitalisation, and the market of print media is far from an exception to that rule.

The in 1843 founded British journalism group The Economist had their fair share of economic downturn, and have seen their print circulation go down and their advertising and subscription revenue consequently.

However, as for most disrupted markets, the customer needs didn’t necessarily shift. The job that the market tries to get done is essentially still the same—the way they like to do that just changed.

The market didn’t lose their need to capture treasurable moments, Kodak just failed to move with the digital needs from their market.

The market didn’t lose their need to have on-demand T.V. entertainment from the comfort of their homes, Blockbuster just didn’t adapt to an even quicker and hassle-free way of delivering that entertainment to the homes of the market.

The audience of The Economist still wanted to be informed about international topics that would enlighten their minds. They just didn’t want it solely via pieces of paper. And that’s exactly what the journalism mogul did.

Business Model Innovation

Whereas loads of incumbent businesses cling on tightly to their current products/services or types of revenue streams, most successful corporate innovations come from altering the business model from the ground up.

Partly ditching what made the company a profitable conglomerate is downright scary and surely not without risk. I can imagine that the terms “cannibalisation” and “harm current P&Ls” were shouted more than once at Daimler’s boardroom around 2008, the year Car2go was founded. At first, it would seem odd that a business that has grown to €164 billion in revenue by selling cars to consumers would originate a business that advocates for a world without car-ownership.

But according to Daniel Zhang, the successor of Jack Ma’s legacy at Alibaba, that’s exactly what any successful business has to do. It’s either you do it yourself. Or others will. And according to the latest moves by Volvo and Renault, it seems they would’ve been glad whenever they had conversations alike Daimler back in the day.

“Every business has a life cycle, if we don’t kill our existing business, someone else will. So I’d rather see our own new businesses kill our existing business.”

— Daniel Zhang, CEO of Alibaba Group (source)

Through continuous globalisation (potentially huge market) and digitalisation (decreasing cost of developing software and information & market transparency), the benefit of entry rises and the barrier to entry moves asymptotically down. This means that whenever a vertical is underserving their market it becomes increasingly inevitable that competitors will arise and serve them well, even in verticals formerly unaccustomed to disruptors like the freight forwarding market that’s shaken up by Flexport and student education through Lambda School.

The lesson here: The market always wins.

And will continue to win more.

And how did The Economist listen to the market?

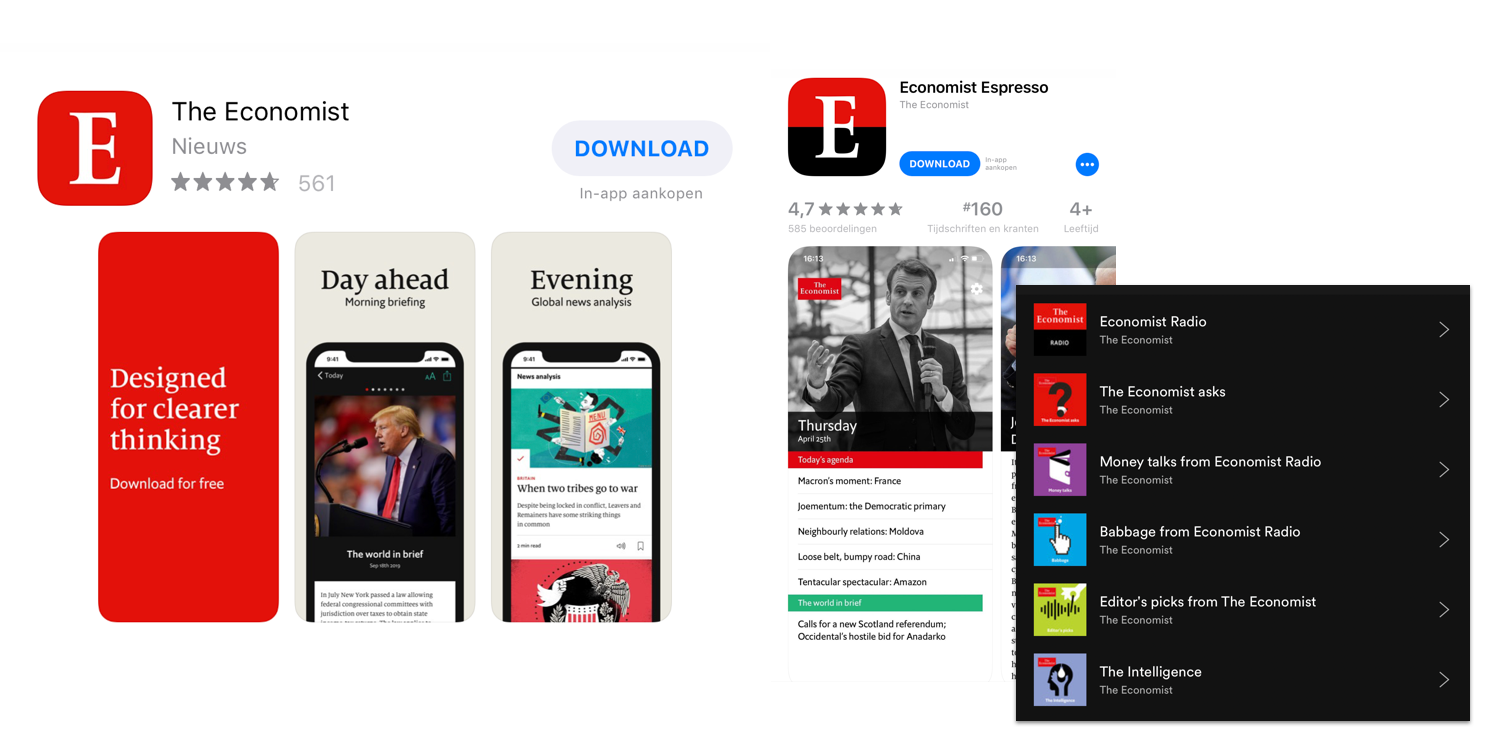

The publisher launched their first online publication already in 1996, but have only truly intensified their digital-first products last couple of years. Through their relatively novel propositions such as Economist Espresso and crafting bite-sized news moments in their general mobile app and podcasts, fitted to the busy lives of professionals, they fulfil the jobs-to-be-done of their audience.

Whereas the products above seem to fit in nicely into our lives today, the Economist continues to move forward and stay ahead of the curve and is testing with a virtual reality app and was testing with Snapchat content in 2016 (which 176-year-old is doing that!).

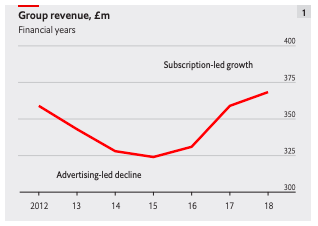

It’s noteworthy to illustrate that although a lot of business innovation may feel like a cash-devouring hobby, The Economist sees profits rising year-over-year. It makes it even more remarkable when one looks at their operating profit versus other media companies alike such as The Guardian which reported losses exceeding tens of millions of pounds in 2018 whereas The Economist Businesses announced it had £22 million in profits with almost £262 million in revenue in the same year.

Mindset Leads The Way

One question always arises from these, from my perspective, success stories: How did The Economist accomplish this change? Obviously, the decline in advertising revenue as a result of decreasing circulation signalled something needed to happen, however not on how to achieve it.

Up until this day, loads of folks tend to believe it’s solely creativity—a brilliant idea if you will—that leads towards success. But from my experience this is way less of a good predictor of success than customer obsession.

One company that embodies such an obsession is Amazon, whereas Jeff Bezos is famous for making sure that every meeting has at least 1 empty chair that represents the customer, to make sure the #1 stakeholder isn’t forgotten during decision-making.

During my quest to learn more about the organisation and the teams operating at The Economist, I’ve come to hypothesise that it’s the mindset towards serving their readers and target audience that guided them to developing successful products and propositions.

“Focus is more on value over volume”

— Marina Haydn, Managing Director of Global Circulation (source)

The most important observation is not necessarily that they are heavily customer-centric, but more that throughout the entire organisation this seems to be the mindset on the work that it’s employees produce.

“Our products team believes in solving business problems by solving customer problems. So we kicked off by talking to readers to find out more about their motivations and frustrations.

We then worked with UX researchers, designers, developers and editors to come up with hypotheses on how we could use our products to meet readers’ needs. We practice design thinking: we did lots of brainstorming and sketching, built prototypes, tested them in front of real users, and iterated based on their feedback.”

— Sunnie Huang , Newsletter Editor at The Economist (source)

This clearly resulted in digital products with a phenomenal adoption rate and subsequently in a method to monetise their reach—a state of product-market fit. But not only in the innovation phase The Economist uses methods such as customer development and design thinking, also the teams that are responsible for expanding the growth rate and monetisation metrics seem to utilise methods that evolve around adopting multidisciplinary teams that work data-informed towards their goals.

‘’[..] forcing previously separate departments to collaborate. At The Economist, Rawling has created three cross-functional “tribes” to work on app, website and newsletter projects. These teams have a combination of editorial, product, marketing, analytics and design experts. They’re working on redesigning the app so people use it more regularly.’’

— Anna Rawling, VP of Digital Engagement and Retention (source)

Wrap-up

This leads me to conclude that The Economist’s meltdown has been turned around through a period of radical innovation that required an organisation-wide mindset that is obsessed about serving the customer’s needs and successful monetisation from that value creation.

Point here is that if a 176-year old media company, a vertical notoriously known for being conservative, can succeed virtually any organisation can with the appropriate measures, such as:

- An organisation-wide culture of putting the customer’s needs first and structure the business and team accordingly

- The willingness to invest significant funds

- The belief that the only way forward is innovation, instead of solely holding on to existing business models

So whether you need Jeff’s technique to have trivial empty chairs in the room or have to break down current functional silo’s to make sure your organisation won’t follow in the footsteps of Kodak or Blockbuster, learn the current and future needs of your audience and act on it. Or somebody else will.